Automotive

Achieve compliance and guard against threats.

Explore More

Education

Keep schools safe for students and teachers.

Explore More

Finance

Protect data, transactions, and operations.

Explore More

Government

Guard against threats to local and national agencies.

Explore More

Healthcare

Meet regulatory requirements and protect privacy.

Explore More

IT Service Providers

Optimize resources and secure organizations.

Explore More

Manufacturing

Reduce risk and keep operations uninterrupted.

Explore More

Software & Technology

Focus on innovation and not cyber threats.

Explore More

Trucking

Secure transportation for the road ahead.

Explore More

Does your business satisfy security regulations?

Learn how your industry, services, and location can impact your compliance posture.

Get StartedAbout us

Learn more about Coro and the people behind it.

Explore More

Careers

Join the most innovative organization in cybersecurity.

Explore More

Press

Catch up on the latest Coro news and updates.

Explore More

Contact

Get in touch with our sales or support teams.

Explore More

Events

Catch up on the latest Coro events.

Explore More

Does your business satisfy security regulations?

Learn how your industry, services, and location can impact your compliance posture.

Get StartedStart a Trial

Watch a Demo

Contact Sales

Become a Partner

Compliance Survey

Get Support

Start a Free Trial

Try Coro for Free for the Next 30 Days

"*" indicates required fields

Watch a Demo

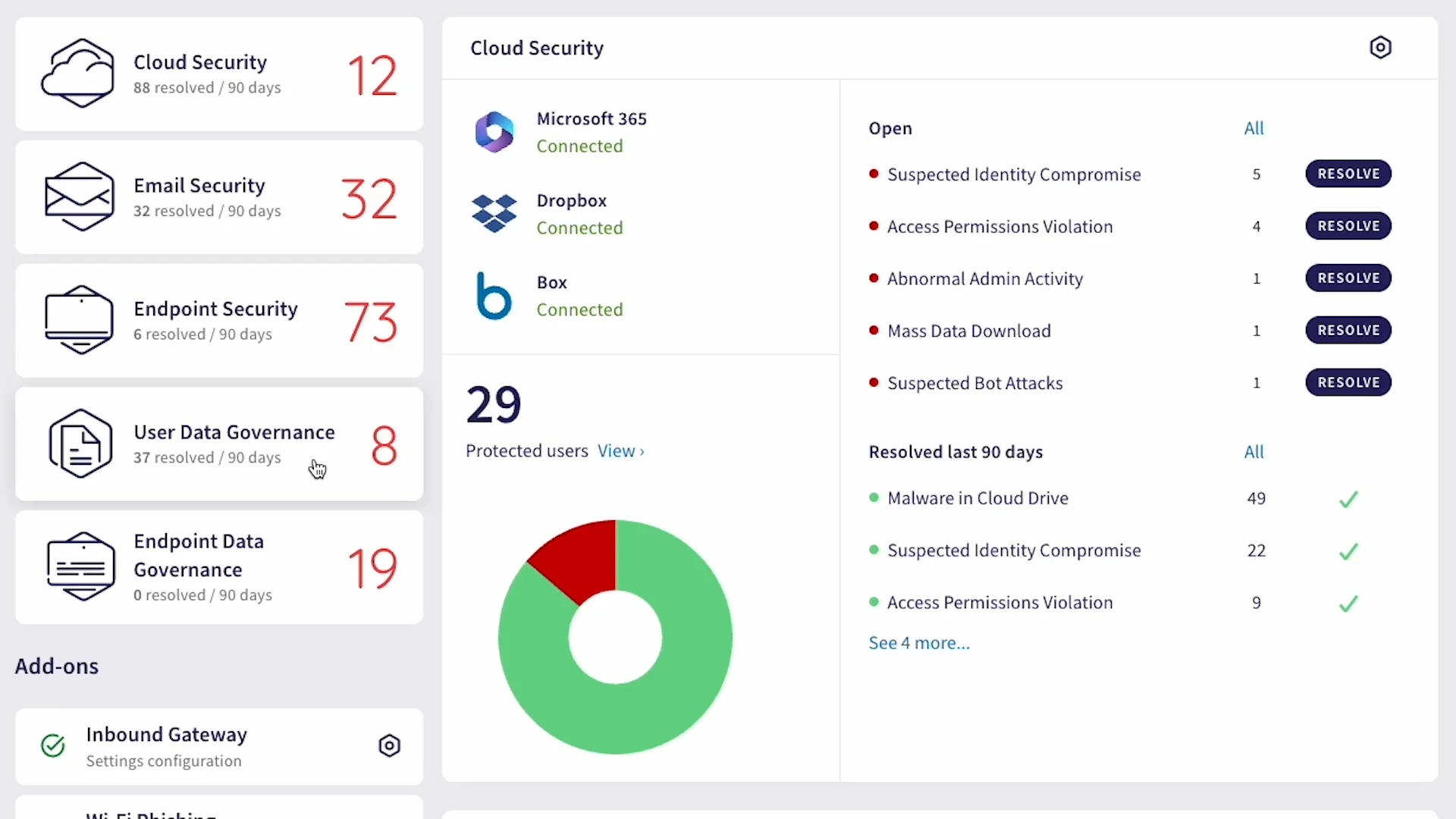

Explore our collection of recorded product demonstrations to witness Coro in action.

"*" indicates required fields

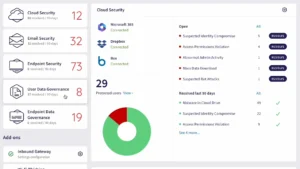

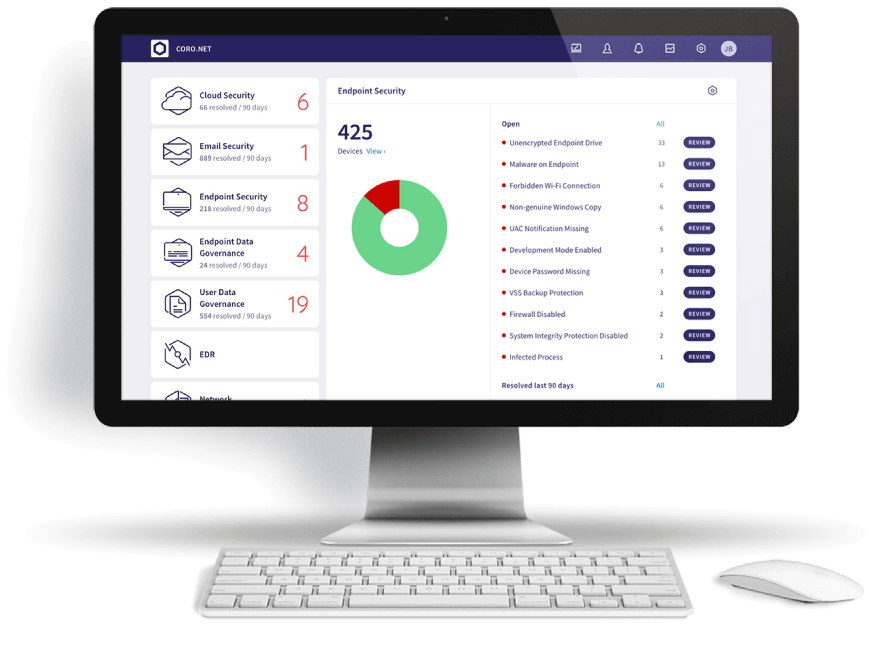

See how much time you could save with Coro guarding your business:

Instantly handle 95%+ of email threats

Monitor cloud app security from a single dashboard

Protect devices across the threat landscape

Prevent data loss with a deceivingly simple solution

Contact Sales

Receive comprehensive information about our product, pricing, and technical details straight from our specialists.

"*" indicates required fields

Become a partner today

Turn your cybersecurity business into a revenue center

"*" indicates required fields

Build Your Compliance Report

Does your business satisfy security regulations? Take the survey to learn how your industry, services, and location can impact your compliance posture.

Take the Compliance Survey